Do Lighter Racecars Get More Points?

Introduction

Do lighter racecars go faster? Does mass even matter? Should a mass target be a key design goal? Low mass is often taken to be a virtue in FSAE/FS racecars, and often chosen as a design strategy for improvement in performance. But does low mass really pay off? Past FSAE results are examined to discover their sensitivity to mass. Mass is considered both as an independent parameter, and in combination with other parameters. Arguments are advanced on the basis of racecar physics. Design strategies are proposed that consider mass in combination with other key racecar parameters. Mass is demonstrated to be important, but not independently so.

Mass as an Independent Parameter

Published FSAE results include the racecar curb masses, which are measured and recorded at weigh-in. Total competition points may be plotted against mass to illustrate its actuarial effect. Figure 1 shows the 2025 IC results. These results are filtered to include only racecars that finished all five dynamic events – Acceleration, Skidpad, Autocross, Endurance (with time points instead of just with lap points), and Efficiency. This leaves just 44 qualified data points out of the 106 entries on-site. These actuarial results merely show how one attribute (total points) is associated with another attribute (curb mass), and do not indicate a causal link. To be more thorough, other years and competitions should also be studied. This task extension and its conclusions are left to the interested reader.

Figure 1 – Relation of total competition points (for racecars completing Acceleration, Skid Pad, Autocross, Endurance, and Efficiency events) to racecar curb mass in the 2025 FSAE/IC Competition.

Figure 1 shows that low mass is associated with some success. The trendline offers -1.95 points per kg (i.e. reducing mass by 10 kg offers a benefit of 19.5 points). But the scatter is high (mean deviation from the trendline is 103 points – 10%), so that the benefit probably also depends on other factors, and is not simply guaranteed by the mass figure. Looking at individual data points, the racecars with the lowest masses have good point totals, but not the best, while the highest points are associated with racecars whose mass is more robust. This suggests that mass is important, but not decisive as an independent parameter.

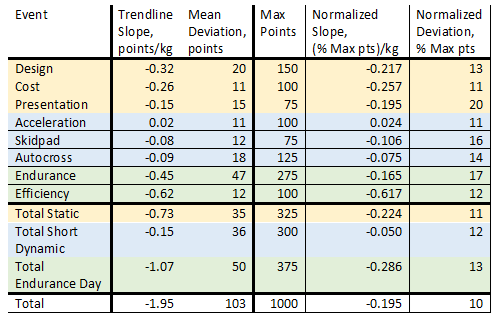

Drilling down, these results may be divided into individual events in order to suggest which events might be most influenced by mass. Table 1 shows the regression results by event. Results are presented both as event points contributing to the competition maximum of 1000, and as points normalized to the maximum points allocated to each event.

Table 1 – Regression summary by event of competition points to racecar mass in the 2025 FSAE/IC competition (for racecars completing all dynamic events). Includes points normalized to the maximum points allowed in each event.

Table 1 shows that static event points – Design, Cost, and Presentation events - are a little more strongly influenced by mass than total points are (as demonstrated by the total static normalized slope). In Design, one might at first imagine that this reflects a judging bias towards lighter racecars; although it is surely more accurate to conclude that racecars which have been carefully designed to reduce mass have also been carefully designed in other judge-able ways. Low mass might then be taken as a symptom of high-scoring design instead of as a cause. The same premise might hold for Presentation – a better prepared team tends to design better (i.e. lighter) and also presents more effectively. In Cost, we might additionally observe that lighter cars have a lower material cost.

Table 1 shows that short dynamic points – Acceleration, Skidpad, and Autocross events – are (somewhat surprisingly) less influenced by mass (as demonstrated by the total short dynamic normalized slope). Indeed, points in Acceleration appear to improve with higher mass (although the associated scatter is wide). This might suggest that, on average, teams that put more mass into a racecar tend to slightly over-compensate with an added increment of thrust. Another suggestion is a dominance of the intricacies of launching dynamics over the simple effects of accelerated mass. Skidpad success shows some sensitivity to reduced mass, though at a lower normalized rate than total points. This might result from the effect of ‘better designed racecars are lighter and also perform better’. Autocross results are similar to those of Skidpad.

Table 1 shows that endurance day points – Endurance and Efficiency – are most strongly improved by reduced mass (as demonstrated by the total endurance day normalized slope). Endurance points are only a little less mass-influenced than total points, and twice as influenced (on a normalized basis) as Autocross. This may be an interesting subject for further study. It could be that even though the courses are similar, the longer Endurance race in a heavier racecar puts greater strain on the racecar’s systems and on its driver. But the real outlier result is the sensitivity of Efficiency points to mass, influencing at three times the normalized rate of total points. This might be a ‘better designed’ effect, or there might be a driving profile effect of lots of full throttle accelerations without the inefficiencies of initial launch.

Based on this cursory analysis of the 2025 FSAE/IC results, it does not appear that racecar mass, as an independent parameter, can be considered to be an independent driver for total competition points. Lower mass is shown to associate with higher points, but perhaps more as a symptom of a successful and very complex design and racing process, and less as an independent cause. Scatter in the mass impact is high, suggesting that many other racecar attributes also have a significant impact on competition points.

Again, all of these correlations are actuarial. They are about what happened, but they are not about how it happened. Closing this causal loop would require a thorough set of logical or analytical behavior models validated by experiments.

Do Lighter Racecars Go Faster?

Changing direction, let us examine mass influence on points from a racecar physics point of view. Racecar physics suggests that FSAE/FS racecars, operating on FSAE/FS event courses, are far more limited by acceleration than by top speed or any other performance measure. This is why g-g plots (longitudinal, lateral, and braking acceleration potential, measured in g’s, on a polar plot) are so important in a team’s design process and in the Design event – in design targets, in design calculation, in design concept simulation, and in physical validation testing. The racecar consistently pulling more g’s may also be expected to pull more points. Acceleration is the ratio of thrusting force to attenuating mass. Less mass must mean more acceleration, as long as thrust is not reduced in proportion.

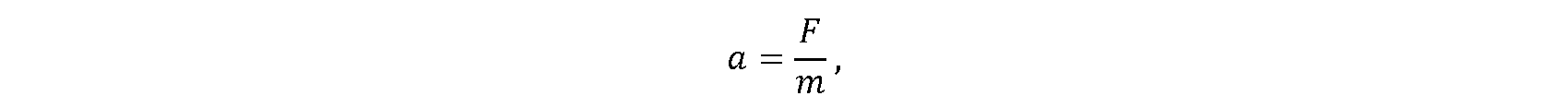

As a simple case, consider longitudinal acceleration. Acceleration is thrust from the powertrain (acting through the drivetrain, suspension, and tire patches) divided by vehicle mass:

or with a little more detail, in the IC case:

where a is longitudinal acceleration, bmep is engine brake mean effective pressure and V_d is engine displacement (or the electrical powertrain equivalents to bmep and V_d that parameterize shaft torque), R_DT is the total powertrain/drivetrain reduction ratio, n_m is its efficiency, r_w is the rolling wheel radius, drag force includes shaft, aerodynamic, and other frictional items, and m is our friend, total vehicle mass (with driver, this time). Many of these parameters vary with racecar speed. Acceleration is further limited by suspension and tire characteristics in a manner that is less linear, but certainly as important.

Clearly, longitudinal acceleration depends strongly on mass. But it also depends on the powertrain’s torque and arrangement. Considering the IC case, if a heavier and more powerful engine is mounted, then mass would go up some (by the additional mass of the bigger engine, plus that mass’s reflection through the rest of the racecar’s structural masses and support system masses). But the more powerful engine’s torque might go up even more, in proportion to mass, resulting in a higher acceleration (and a point more in the upper right quadrant on Fig.1). And so mass and torque are both important, but in combination rather than independently.

Mass as a Dependent Parameter

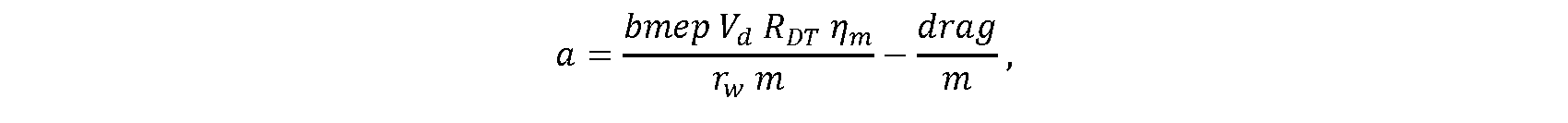

From the physical view, mass matters to FSAE/FS longitudinal acceleration performance, but only as a dependent parameter - as a part of the thrust-to-weight ratio (coupled through speed to the power-to-weight ratio). The results reported by FSAE do not support calculation of this ratio for the competition field - bmep, R_DT, n_m, r_w, and drag are not available. But V_d is. And if some scatter in bmep and drivetrain parameters is accepted, then V_d/m (going back to curb mass) might serve as a proxy for a whole-vehicle thrust-to-weight ratio. Plotting Acceleration points against V_d/m shows:

Figure 2 - FSAE/IC 2025 results for Acceleration as a function of the ratio of engine displacement to curb mass.

The left side of Fig.2 is populated by racecars with small engines or high mass. The right side contains racecars with large engines or low mass. Figure 2 demonstrates a trendline gain of 28.6 Acceleration points per unit cc/kg increase, and shows less scatter than Fig.1. The highest Acceleration points come from a displacement-to-mass ratio of about 3 cc/kg. But as shown by the individual data points, increasing to 3.6 cc/kg does not result in an increase in acceleration points. It may be that the 3 cc/kg racecar overshadows the 3.6 cc/kg racecar in terms of: better bmep; optimized drivetrain, suspension, and tires; or an indefatigable effort to drive out frictional and aerodynamic drag. So displacement-to-mass ratio is important, but again, not decisive by itself. [In Fig.2, one outlier point was deleted – this racecar has a turbocharged engine with a very high bmep, and so only a low V_d is needed to make the necessary torque, and so V_d/m is much less accurate as a proxy for the thrust-to-weight ratio of this racecar. The deleted racecar achieved a V_d/m of 1.68 cc/kg and an Acceleration score of 92.]

Using racecar physics to create a more insightful combined attribute that tracks more directly with racecar acceleration reduces scatter and more clearly indicates a route to competitive success. But this combined attribute by itself is still not able to overshadow the significant effects of excellent design in the racecar’s propulsion, drivetrain, and traction systems.

What About Lateral and Braking?

The above two sections use longitudinal acceleration (the +x axis on a g-g plot) as an example of consideration of mass effects as an independent or dependent parameter. Similar arguments could be made for lateral and braking accelerations, although the mechanics are more complex. The interested reader will surely benefit from extension of the longitudinal arguments into other axes. This will provide a more complete answer to the question: ‘do lighter racecars go faster?’.

Thrust-to-weight ratio is a lot harder to work out for lateral acceleration. The FSAE results do not provide enough information to estimate this for the field. The ratio is a matter of the tire characteristics, suspension action, and mass properties, and how they combine to create the lateral thrust potential of a racecar. But for a particular racecar for which this design data is known (i.e. yours), the potential lateral thrust-to-weight may be determined from vehicle dynamics. Mixing (verified!) aerodynamic downforce into this analysis will allow a more critical determination of whether the aero package is actually helping the overall racecar to achieve its goals (most often it does not, though for the ones that it does – wow!) Of course, limited driver skill may constrain the lateral thrust-to-weight that is actually achieved. Lifting this constraint may require better cockpit biomechanics, possibly trading a real lateral acceleration for one that exists only on paper. The bottom line for lateral acceleration is that mass plays a key role, but only in combination with other properties and system performances – and not as an independent parameter.

Carroll Smith reminds us that the brakes are the most powerful engine on a racecar. And brakes do matter - Steve McQueen advises his co-driver that “you can out-brake the Ferrari” (Le Mans, right?). Better-braking FSAE/FS cars can extend their braking points and corner faster. Better braking performance (by both braking system and tires) should produce more (reverse) thrust, which improves the braking thrust-to-mass ratio (although this better braking and traction might cost slightly more mass – there is a cost to this benefit, after all). Alternately, a lighter racecar (same brakes/suspension/tires) should decelerate faster. Even better, if an excellent braking system generates more retarding thrust and the racecar also weighs less, then the racecar can brake later and lap faster (as long as the drivers are suitably trained).

So mass matters to the lateral and braking accelerations, as well as to the longitudinal. But mass still matters only as a parameter dependent on other parameters and on the performance of the racecar’s systems, and not as a racecar performance determiner by itself.

Is Low Mass a Virtue?

When a sub-180 kg car rolls up for Design judging, the judges will usually show positive regard for it - unless a case builds up for why it might not live up to the promise of its mass sticker. When a super-230 kg car rolls up, that team will have its work cut out for it, persuading the judges that their racecar’s extra heft doesn’t slow it down. Mass is a proxy figure for lean design. Think of that weigh-in mass as a team’s claim to a level of virtue in lean design. The weigh-in mass is a self-stated bar that the team sets for itself. If the team clears that bar, proving its claim in judging and on the track, then it gathers the associated points. If it doesn’t, then it doesn’t.

Every performance-oriented design agency emphasizes lean design: understanding of the bottom-line goals, requirements, and constraints; understanding of the variations in location, direction, magnitude, and time (this spectrum extends to dynamics and vibration) of the loads and effects that allow the goals to be met; understanding of the strength and stiffness that will allow the machine to handle the fluctuating loads reliably; and putting just enough material in place to do it – optimally. That’s lean design. Too much mass may allow the design goals to be exceeded, but not in any way that impacts points – this is the definition of design inefficiency (lack of leanness). Too little (or improperly distributed) mass may fail to meet the design goals. Lean design, then, is about getting it just right – necessary and sufficient, everywhere in the racecar. Low mass is a good proxy for lean design, but it is only that – a simple proxy.

On the track, all other systems (suspension, propulsion, braking, use of tires) being equal, lower mass should certainly mean a faster racecar that gets more points (given reliability, driver skill, favor or disfavor of the racing gods, etc.). Though simply lightening a racecar that lacks good systems and subsystems will probably not improve its overall performance. Low mass benefits racecars whose systems are engineered to make use of it.

FSAE/FS design takes the discipline of lean design one level further, to a system of systems. The overall racecar is enabled by several necessary systems (vehicle dynamics, propulsion, structural, biomechanics, etc.). In system designs, as subsets of the overall vehicle design, achieving the necessary benefit of these systems (reliable function) is usually relatively more important than their cost increment (in mass, space, complexity, money, etc.) to the overall racecar. To get a high-performing racecar, the overall design and the system designs must all be correct, appropriate, and flawless (or lucky!). While mass is a fair proxy for overall design, the scatter in Figs.1 and 2 is mostly due to differences in systems performance.

Design for Reduced Mass

Should mass be an FSAE/FS design target? Possibly, but not a primary target. Accelerations (and accelerations as functions of speed) should be the design-to targets. But mass drifting up during the design process can only hurt, and so a mass target, divided up among systems, is useful in design project management – to keep the design team on track and in line to produce a triumph of lean design. Overall and system mass goals are useful to keep a design from drifting. Cost works in a similar way.

In FSAE/FS design, mass is often not given a set target. It is instead desired to be ‘as low as possible’. As a design strategy, ‘as possible’ design at its worst can be a license to ignore, resulting in a heavy, slow racecar. But at its best, ‘as possible’ suggests the intelligent optimization of mass while meeting other quantitative constraints, such as racecar and system performance goals. If faithfully carried out, an ‘as possible’ design process can be managed to achieve excellent results.

Whether mass is a goal of the design process or not, the mass of the current state of design must be monitored. Consider the braking system designer. The braking system design cannot be assessed against overall racecar deceleration goals unless the vehicle mass is known. Every evolving system design contributes to an evolving vehicle mass. Most successful vehicle design processes follow a ‘design spiral’. The systems are designed for the current whole vehicle properties (mass, centers, gyradii, dive/squat). The resulting system masses are then summed to produce updated whole vehicle mass properties, and then the system designers address this updated state of design in further iterative design spirals. If the design process is successful, these spirals will converge. It is better to follow the spiral and get systems that are perfectly matched to what the whole vehicle truly becomes, than to ignore the spiral and get systems that are perfect only in their own bubble.

Conclusion

So do lighter racecars get more points? On the whole, yes – a lot. But mass by itself is not a performance determiner. This is clear from the trendline and high scatter of Fig.1. Mass is a key parameter of the racecar, but no more important (and perhaps less) than tire grip, driving torque, and flawless systems for delivering these. Your racecar design has to get all of this right. But if you do, you can win.

Acknowledgment

“Thanks!” to USC’s IC Chief Engineer for the illuminating discussion in 2025 Design Finals that inspired this article.